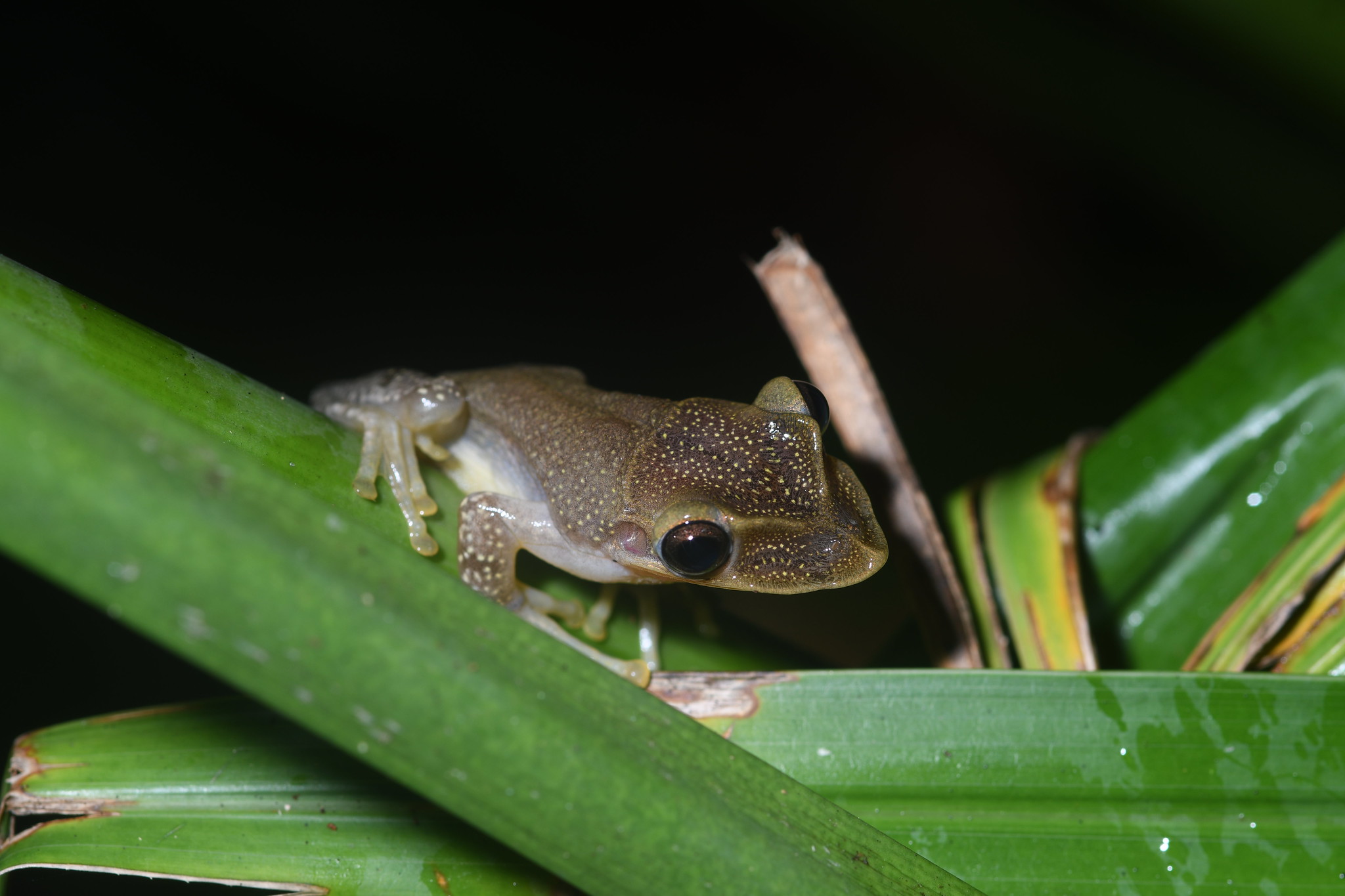

Found many of these frogs under a wet trash bag in a back yard in Mérida, Yucatán. I made use of a handheld flash with a remote trigger for lighting, and a Sigma 105 mm as my macro lens.

These frogs do not seem to match with any of the local frogs reported in Julian C. Lee's field guide to the amphibians and reptiles of the maya world.

From a reverse image search, I mostly found images of the green house frog Eleutherodactylus planirostris. Eleutherodactylus planirostris is native to Cuba and the Bahamas, and is often introduced with plants that come from green houses in those areas. These frogs go from tadpole to frog while still inside of the egg, which explains why the baby frogs are so small.

The visual aspect, the incredibly small baby frogs, and the fact that they were found in a back yard in the city with greenhouse plants, all lead me to conclude that it is likely Eleutherodactylus planirostris.