Here's the arguments :

Throughout the nineteenth century and up to the 1920s, the USA was the fastest growing economy in the world, despite being the most protectionist during almost all of this period.

(source)

(Source : p.40 of Economics and World History, by Paul Bairoch, 1993)

What is especially interesting to note here is that many US intellectuals and politicians during the country's catch-up period clearly understood that the free trade theory advocated by the British Classical Economists was unsuited to their country.

Reinert reports that, due to this concern, Thomas Jefferson tried (in vain) to prevent the publication of Ricardo's Principles.

Reinert also cites from List's work the comment by a US Congressman, a contemporary of List, who observed that English trade theory 'like most English manufactured goods, is intended for export, not for consumption at home'.

(...)

By commercial and industrial regulations attempts were made to restrict the [english] colonies to the production of raw materials which England was to work up, to discourage any manufactures that would any way compete with the mother country, and to confine their markets to the English trader and manufacturer.

(source)

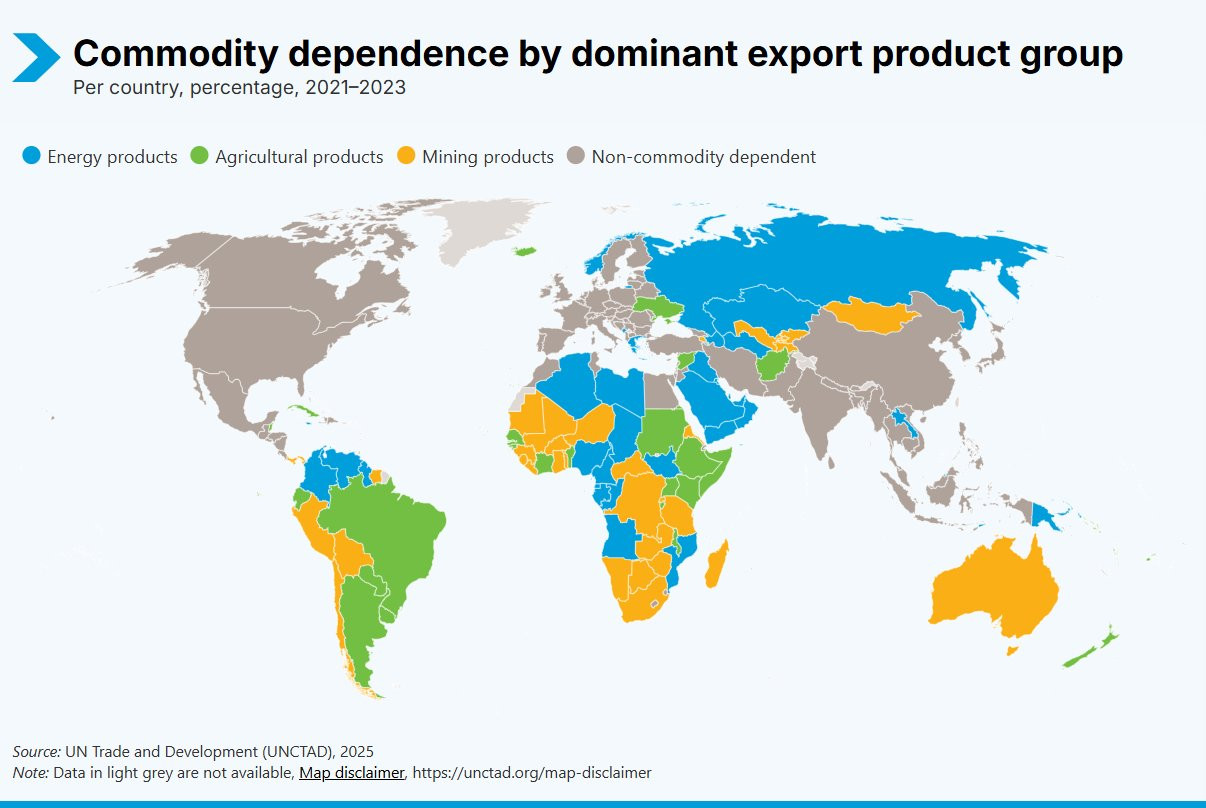

World commodity export dependence(, All commodities, per country, percentage, 2021–2023) :

(source)

However, it seems to be a remarkable coincidence that so many countries that have used such [protectionist ]policies, from eighteenth-century Britain to twentieth-century Korea, have been industrial successes, especially when such policies are supposed to be very harmful according to the orthodox argument.

(source)

There were many other tools[ than tariff protection], such as export subsidies, tariff rebates on inputs used for exports, conferring of monopoly rights, cartel arrangements, directed credits, investment planning, manpower planning, R&D supports and the promotion of institutions that allow public-private cooperation.

Addition(, source), which also applied to a lesser extent to (other useful anti-communist regimes, and )India(, source) through the public law 480, perhaps in order to bring it closer to the west and further from its socialist neighbours.

The problem is that the productivity gap between today's developed countries and developing countries is much greater than that which used to exist between the more developed and less developed NDCs[Now-Developed Countries] in earlier times. This means that today's developing countries need to impose much higher rates of tariff than those used by the NDCs in the past, if they are to provide the same degree of actual protection to their industries as that once accorded to the NDC industries.

(source)

When in the late nineteenth century the USA accorded an average tariff protection of over 40% to its industries, its per capita income in PPP terms was already about three quarters that of Britain(, $2,599 vs. $3,511 in 1875). (...) Compared to this, the 71% trade-weighted average tariff rate that India had just prior to the WTO agreement - despite the fact that its per capita income in PPP terms is only about one fifteenth that of the USA - makes the country look like a veritable champion of free trade. Following the WTO agreement, India cut its trade-weighted average tariff to 32%, bringing it down to a level below which the USA's average tariff rate never sank between the end of the Civil War and the Second World War.

(source)

It's true that India was one of the fastest countries to rise(, compared to Latin America, Africa, or the Middle-East)(, the data is PPP-adjusted, and yes, i know that the g.d.p. has too many problems to be considered a good indicator, however i don't know of a better alternative on OurWorldInData or elsewhere, source) :

However, the indian growth(, criticized a few days ago b.t.w., i.d.k. 🤷,) can't simply be attributed to a diminution of the tariff rates because many countries lowered theirs without witnessing such growth, and he argues that this diminution led to a lack of industrialization.

Beyond his solutions, it's the observation below on the failure of our advices in the 80s-00s, that interest me the most.

Following the WTO agreement, Brazil cut its trade-weighted average tariff from 41% to 27%

The plain fact is that the Neo-Liberal 'policy reforms' have not been able to deliver their central promise - namely, economic growth.

When they were implemented, we were told that, while these 'reforms' might increase inequality in the short term and possibly in the long run as well, they would generate faster growth and eventually lift everyone up more effectively than the interventionist policies of the early postwar years had done.

The records of the last two decades show that only the negative part of this prediction has been met.

Income inequality did increase as predicted, but the acceleration in growth that had been promised never arrived.

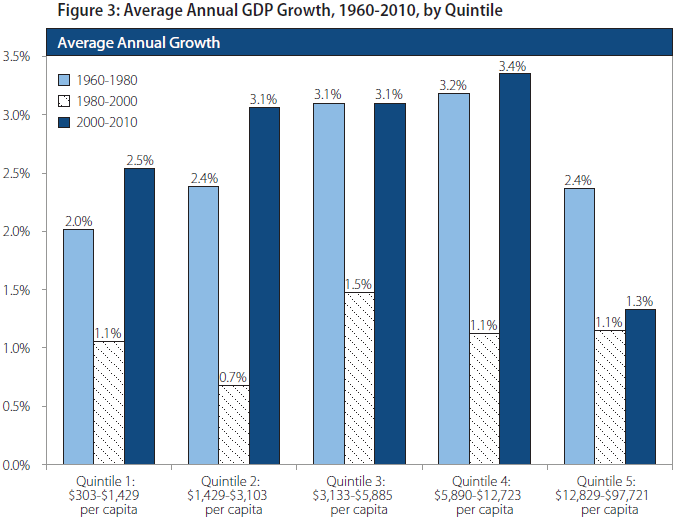

In fact, growth has markedly decelerated during the last two decades, especially in the developing countries, when compared to the 1960-1980 period when 'bad' policies prevailed.

According to the data provided by Weisbrot et al. in the 116 (developed and developing) countries for which they had data, GDP per capita grew at the rate of 3.1% p.a. between 1960 and 1980, while it grew at the rate of only 1.4% p.a. between 1980 and 2000.

In only 15 of the 116 countries in the sample - 13 of the 88 developing countries — did the growth rate rise by more than 0.1 percentage points p.a. between these two periods.

More specifically, according to Weisbrot et al., GDP per capita grew :

- at 2.8% p.a. in Latin American countries during the period 1960-1980, whereas it was stagnant between 1980 and 1998, growing at 0.3% p.a.

- GDP per capita fell in Sub-Saharan Africa by 15%(, or "grew" at the rate of -0.8% p.a.) between 1980 and 1998, whereas it had risen by 36% between the period 1960-1980(, or at the rate of 1.6% p.a.)

- The records in the former Communist economies (the 'transition economies') - except China and Vietnam, which did not follow Neo-Liberal recommendations - are even more dismal. Stiglitz points out that, of the 19 transition economies of Eastern Europe and the former Soviet Union, only Poland's 1997 GDP exceeded that of 1989, the year when the transition began. Of the remaining 18 countries, GDP per capita in 1997 was less than 40% that of 1989 in four countries(, Georgia, Azerbaijan, Moldova and Ukraine). In only five of them was GDP per capita in 1997 more than 80% of the 1989 level(, Romania, Uzbekistan, Czech Republic, Hungary and Slovakia).

So that's the main argument, which is confirmed by the data available in 2002. However, the growth took-off afterwards :

Here's a 2011 explanation by Weisbrot himself for latin america :

From what i found, Ha-Joon Chang and Mark Weisbrot considered that the growth post-2000 confirmed their criticisms, because the People's Republic of China had the highest growth of all countries while also being the country which disobeyed western recommendations("commands" through the western-controlled unholy trinity based on the imperative to reimburse the national debt).

They'll put forward an (insufficient i.m.o. )increase in the price of raw materials, and a loosening of the enforcement of neoliberal policies after the 2000s, while regretting the absence of industrial strategy for the poorest countries still relying on their export of raw materials.

The All Commodity Price Index was multiplied by 4 !

(source)

So Ha-Joon Chang and Mark Weisbrot still believe in their criticisms pre-2000, and continue to fear for the future with the end of the super growth in China, as well as the upcoming debt crisis with high interest rates : « This is especially true in the past two years as the US Federal Reserve has raised policy interest rates 11 times. This helped push developing countries’ interest rates up by nearly 8 percentage points, which is huge, as well as increasing the cost of borrowing in dollars since the vast majority of countries saw their currencies depreciate against the dollar. This is at a time when the global economy is facing projected economic growth over the next five years that is the worst in decades, as well as the growing burdens of climate destruction and the costs of transition away from fossil fuels. » source

Moreover, the "unholy trinity" is still active(, e.g. europeans will remember Greece and Yanis Varoufakis in 2015, but it's worldwide), with the same "friendly advices" that "unfortunately" ruined the u.s.s.r.(, and most countries of the Varsaw pact,) post-1991.

So we have an apparent 'paradox' here - at least if you are a NeoLiberal economist. All countries, but especially developing countries, grew much faster when they used 'bad' policies during the 1960-1980 period than when they used 'good' ones during the following two decades.

The obvious answer to this paradox is to accept that the supposedly 'good' policies are in fact not beneficial for the developing countries, but rather that the 'bad' policies are actually likely to do them good if effectively implemented.

Now, the interesting thing is that these 'bad' policies are basically those that the NDCs had pursued when they were developing countries themselves.

Given this, we can only conclude that, in recommending the allegedly 'good' policies, the NDCs are in effect 'kicking away the ladder' by which they have climbed to the top.

(...)

In describing the Golden Straitjacket, [Thomas Friedman] pretty much sums up today’s neo-liberal economic orthodoxy : in order to fit into it, a country needs to privatize state-owned enterprises, maintain low inflation, reduce the size of government bureaucracy, balance the budget (if not running a surplus), liberalize trade, deregulate foreign investment, deregulate capital markets, make the currency convertible, reduce corruption and privatize pensions.

(...)

However, the fact is that, had the Japanese government followed the free-trade economists back in the early 1960s, there would have been no Lexus. Toyota today would, at best, be a junior partner to some western car manufacturer, or worse, have been wiped out. The same would have been true for the entire Japanese economy. Had the country donned Friedman’s Golden Straitjacket early on, Japan would have remained the third-rate industrial power that it was in the 1960s, with its income level on a par with Chile, Argentina and South Africa

[Rich countries] account for 80% of world output, conduct 70% of international trade and make 70–90%(, depending on the year,) of all foreign direct investments.

[By 2030, it’s estimated there will be more than 8.5 billion people on Earth with more than 85% of them residing in emerging market countries, source]

More on the "unholy trinity" :

[The IMF and the World Bank] are sometimes collectively called the Bretton Woods Institutions (BWIs). The IMF was set up to lend money to countries in balance of payments crises so that they can reduce their balance of payments deficits without having to resort to deflation. The World Bank was set up to help the reconstruction of war-torn countries in Europe and the economic development of the post-colonial societies that were about to emerge – which is why it is officially called the International Bank for Reconstruction and Development. This was supposed to be done by financing projects in infrastructure development (e.g., roads, bridges, dams).

(...)

Following the Third World debt crisis of 1982, the roles of both the IMF and the World Bank changed dramatically. They started to exert a much stronger policy influence on developing countries through their joint operation of so-called structural adjustment programmes (SAPs). (...) They branched out into areas like government budgets, industrial regulation, agricultural pricing, labour market regulation, privatization and so on.

(...)

In the 1990s, there was a further advance in this ‘mission creep’ as they started attaching so-called governance conditionalities to their loans. These involved intervention in hitherto unthinkable areas, like democracy, government decentralization, central bank independence and corporate governance.

(...)

In the beginning, the IMF only imposed conditions closely related to the borrower country’s management of its balance of payments, such as currency devaluation. But then it started putting conditions on government budgets on the grounds that budget deficits are a key cause of balance of payments problems. This led to the imposition of conditions like the privatization of state-owned enterprises, because it was argued that the losses made by those enterprises were an important source of budget deficits in many developing countries. Once such an extension of logic began, there was no stopping. Since everything is related to everything else, anything could be a condition. In 1997, in Korea, for example, the IMF laid down conditions on the amount of debt that private sector companies could have, on the grounds that over-borrowing by these companies was the main reason for Korea’s financial crisis.

(...)

on seeing Korea’s 1997 agreement with the IMF, one outraged observer commented: ‘Several features of the IMF plan are replays of the policies that Japan and the United States have long been trying to get Korea to adopt. These included accelerating the … reductions of trade barriers to specific Japanese products and opening capital markets so that foreign investors can have majority ownership of Korean firms, engage in hostile takeovers … , and expand direct participation in banking and other financial services. Although greater competition from manufactured imports and more foreign ownership could … help the Korean economy, Koreans and others saw this … as an abuse of IMF power to force Korea at a time of weakness to accept trade and investment policies it had previously rejected’.

(...)

The IMF-World Bank mission creep, combined with the abuse of conditionalities by the Bad Samaritan nations, is particularly unacceptable when the policies of the Bretton Woods Institutions have produced slower growth, more unequal income distribution and greater economic instability in most developing countries

These assertions seem contradicted by such results :

I can only hope that i'm wrong, especially when fearing that the 80s-00s will begin again after the 2030s, but i'm looking for more informations, and i.d.k. in which community to ask that.

I'm also a bit ashamed to speak about one of the most important topics without understanding much of it(, and while launching grave accusations). I'd have preferred to be more knowledgeable before doing it(, especially because it's been years since i've known that), if you have links or books worth reading.

I.d.k. what i was trying to achieve here, perhaps a vague hope to stumble upon someone on the net with the answers i seek.